My Friend Bucky

Indian town Gap, PA October 1951

Had there not been a Korean War, we never would have met. On October, 1951, we were brought together in basic training by his performance, or the lack of it during calisthenics.

After a number of taxing drills, a brawny sergeant on a podium ordered us to do pushups. The pushups were no task for me because I was in very good shape, but the character alongside of me, regardless of what shape he was in was not going to do them. Through the corner of my eye I could see him lying prone on the ground, and merely lifting his head with a groan, as he connected to the sergeant’s cadence.

This is a character I must meet.

We walked back to our company area. The back of his fatigue shirt was billowing over his rear end, the front was covered with the pushup dirt, and he missed a button on his fly. In spite of this, he was a dark and handsome six-footer.

“Hey, I saw you almost do pushups for the sergeant.”

“They’re trying to knock you out until you automatically obey their command,” he replied.

“Why? Pushups strengthen your chest and arm muscles.”

“I have enough strength to push away the crap they feed us in the mess hall, that’s all the strength I need.”

“What’s your name, and where are you from?”

“My name is Jack, but my friends call me Bucky. I’m from the Bronx.”

“A landsman! I’m from the Bronx! Where in the Bronx?”

He lived on the west side of Crotona Park, and I lived in the east. Our upper low class, four story tenements were built in the late 1800s. For an entire block they stood adjacent to one another like cereal boxes in the grocery store. This led to a high density population and a high density of friends.

A whistle blew. We lined up in our platoons on the company street. It was time for lunch. I was in the third platoon, Bucky was in the fourth, which had many New Yorkers or, as Sgt. Roach called them, “a bunch of ref-you-jees.”

Bucky and I got a weekend pass. Sheldon, who lived nearby had a car, and offered to drive us home. On the ride, Bucky kept talking about his beautiful sister, which sounded plausible since he was good-looking. When I asked him for his phone number, he said he didn’t have a phone, but I could write her. This was a total lie. He didn’t have a sister, but it didn’t matter. Our days were hilarious.

After sixteen weeks of basic training, we were full-fledged killers. As a reward, a two-week week delay-en-route pass was issued. I went to Montreal with my mother to say good-bye to my relatives.

At the end of the two weeks, we boarded a troop train at Pennsylvania Station for Fort Lewis, in Seattle, WA. The mess hall was crowded with GIs consequently, the KPs were taxed to the limit.

In order to indicate that our barracks was designated for KP, the mess sergeant wrote a large “KP” on the back of our fatigues shirts with white chalk. He told us that a bus was going to pick us up at 5:00 AM. Upon returning to our barracks, Bucky suggested that we remove our shirts, shake off the KP, and we’ll sleep in the latrine. Although it was damp and uncomfortable, we avoided KP for the entire next day.

Bucky and I were standing at the Seattle pier waiting to board a ship that was going to take us to Japan. He was anxious. He looked up at the huge M.S.T.S. Simon Buckner and said,

“I went rowing in Crotona Park lake, and I got seasick.”

No sooner was the anchor removed from the ocean bed, than Bucky became nauseous. He spent the all the days of our cruise retching in his cot.

It was late April. After eighteen days, we arrived in Yokohama, Japan. Six days of processing, led us to a ship headed for Inchon, Korea. I don’t know who he told, or when he told the army about his medical experience. He told me that he said that he lived near The Bronx Hospital and absorbed a lot of medical procedures from that building.

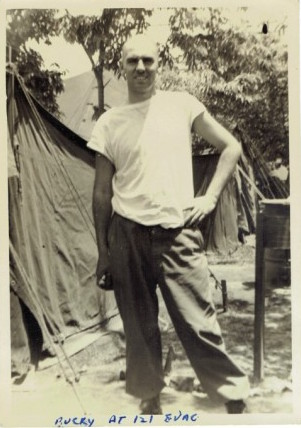

Upon leaving the ship, we became property of the Third Infantry Division. Our train heading north eventually stopped alongside a waiting truck. Among the names called out was Bucky’s. He was assigned to the 121 EVAC,, a hospital that received the GIs who were severely wounded. As he left, he told me that the medics needed him.

Bucky outside the 121 EVAC hospital.

The train moved on. We arrived at the Third Infantry Division battalion headquarters. From there, in a pouring rain, the rest of us were assigned to frontline infantry units.

I didn’t hear from Bucky for a few weeks. How he found my address, only he could tell. He kept sending me letters in envelopes addressed to him. He crossed out his address and scribbled mine in the remaining space.

“The pilots are betting 2 to 1 that the war will end in two weeks.” The truce was agreed upon one year later.

“Innerfeld (we knew him) was brought in. His face was ripped open, and his tongue was torn by a short round from the company next to yours. I was up with him for two days. Check on your mortar squad to see if they know what they’re doing. I’ll see you when you get off the MLR (frontline).”

Six weeks later, Bucky did see me when we finally went to the rear for replacements and training. How did he find me?

It was a day in June, in the distance, I saw a figure walking towards me that resembled Bucky, but he appeared to be much wider and paunchier than the Bucky I knew. Hidden behind his fatigue shirt were a dozen cans of Chocolate Cow (chocolate drink).

“Here. Don’t share it with anyone, it’s for you.”

If anyone knows the infantry, there’s no such thing as, “it’s for you”.

His last words were, “There are too many casualties. You have to get out of here, ”

I’m sure he would have found a way, I didn’t. Bucky returned to his EVAC. He may have lost my address because the letters stopped coming.

After seven months in Korea, I was sent to Japan to accompany untested troops for the invasion of North Korea. It didn’t happen. Truce talks were still going on.

Ten months later, I returned to the U.S. I was sent to Camp Kilmer, NJ for discharge processing. Among the many GIs standing around and waiting for their release was Bucky. Any sane person would be standing on the asphalt path. Not Bucky. He was standing in a four foot square coal receptacle near a barracks, with lumps of coal beneath and around his shoes. The bottoms of his khaki pants were nearly as black as the surrounding coal. Why did he do this? I’m sure he couldn’t give anyone a rational explanation.

The army taught me well, but I was 23 years old without any civilian skills. With the GI Bill, at $110 dollars a month, I was accepted by the City College of NY. What was Bucky doing? Why not visit him?

I walked across Crotona Park to Fulton Ave which was adjacent to the Park. He was spread out on a sofa, wearing his pajamas watching American Bandstand. Before I could start a conversation, his mother came in protesting that Jack was corresponding with a girl in Korea.

“If I could get her address, I would tell her he’s a bum. He doesn’t work, and lays around all day watching TV.”

After she left, Bucky told me that he was applying to the University of Brussels.

“I’m going to become a doctor.”

Placing that statement into the trash bin, I asked him what he really planned on doing. “I had completed two years at Long Island University and they’re going to accept me.”

The University of Brussels accepted Bucky into its medical school, but almost as soon as he was accepted he was expelled by his anatomy professor. The class was studying surgical skills. As Bucky was honing his expertise on a cadaver, the professor came by, saw the mess and called out,

“Praver, you use that scalpel like an American conquistador. Get out of here!”

Bucky returned to the U.S. undaunted, he was determined to become a doctor. He applied to the University of Padua’s medical school in Italy, and was was accepted. The teachers supplemented their meager salaries by selling their lectures in English. Work on a cadaver by the students at that time was not permitted.

Bucky met, Lucceta, who came from a comfortable family in Gallipoli, Italy. He married her in Gallipoli. During intersession at the University, they returned to Lucceta’s home. Again, when Bucky was not studying, he was sprawled out on her parent’s patio, setting his roots into the cushion of a chaise lounge. Lucceta’s mother, like Bucky’s, tried to get him to budge, but to no avail.

Lucceta’s brother was a doctor, a successful graduate of the University of Padua. At the behest of Lucceta, he would call the University to check on Jack’s grades. If Jack wasn’t doing well in a class, he would get a raccomandazione, i.e. a recommendation, or a passing grade . They could be seen scattered throughout his transcript. It’s not that Jack was stupid, quite the contrary, he would always take the path of least resistance.

Upon graduation, Bucky and Lucceta came to the U.S. Jack received an internship at University Hospital in Newark, NJ. During a procedure, when he was assisting a surgeon, the doctor said OK to a nurse. Bucky who was clamping an artery thought the remark was directed at him. He unclipped the forceps and blood squirted up to the overhead light. At that point Bucky decided he would prefer to deal with patients who needed psychiatric help, rather than approach another blood vessel.

Bucky took his licensing exam and passed. He applied for and was accepted as a resident at Manhattan Psychiatric Center on Ward’s Island, Manhattan. He had to move from his apartment in Newark, to a place with reasonable rent and an easy commute. He asked me if I would help with the move. My girlfriend, Sheila and I were happy to assist.

On the morning of the move, Bucky’s brother, Paul and his wife invited Sheila and I to their home in Queens for breakfast. I left my car at their home then Paul drove us to Bucky.

Upon arriving at Bucky’s apartment building, a huge moving van was standing at the entrance. Bucky’s brother left to carry some odd pieces of furniture to the truck. Lucceta followed, bringing some smaller items, while Bucky was sitting on a bench entertaining his daughter, Leslie.

“What’s your apartment number Bucky?”

“Don’t bother. My brother and Lucceta will finish loading the truck.”

Paul shut the rear doors. Bucky, Lucceta, their daughter Leslie, and Sheila went into Paul’s car. I was left standing on the sidewalk.

“Hey. Wait for me.”

“Stay there Danny. You’re driving the truck.”

I stood, frozen. The largest vehicle I ever drove was a four-door sedan. OK, why not give it a try. I climbed up, and moved the seat forward. Immediately, I was intimidated by a diagram of the multiple gears.

“Follow me,” shouted Paul. “If you get lost, I’ll wait for you on the Cross-Bronx Expressway.”

Follow him? Could I start this colossus? What? Wait? Wait where? On the Cross Bronx Expressway? It’s a crowded road that extends from the Bronx to The Hutchinson River Parkway.

I turned the key; the motor hummed. I knew first gear. The truck moved as I shifted to 2nd gear. After four blocks, I lost Paul. Where was he? What am I going to do with the gears when I have to pay the toll on the NJ Turnpike? I can’t keep it in drive.

Rivulets of sweat trickled down my T-shirt, and then blotted by the rear of my seat. I felt a chill. Just like I did at the apartment building, I’ll stop, pay the toll, and start the truck again. I stopped, paid the toll, but the truck stalled when I tried to start it. Honking horns from infuriated drivers added to my tension.

I put my foot on the clutch, placed the truck in first gear, and was on my way to the George Washington Bridge – another toll – another stop. This time I was a veteran. I put my foot on the clutch, paid the toll and I was barreling down the Cross-Bronx Expressway when I saw Paul’s flashing lights waiting under an underpass. Fortunately he saw me coming and maneuvered his car in front of the van.

Tailgating with this truck was nearly impossible, but there was no way I was going to lose Paul. Where were we going? Finally, the last toll on the Whitestone Bridge, and then to a garden apartment complex in Glen Oaks, Queens.Finally, I parked the van.

Legs of rubber carried me to my car. Sheila drove me home. In appreciation for my help, Lucceta invited Sheila and I for a Saturday lunch. She was making her classic tuna fish in tomato sauce with linguine. Meanwhile Bucky showed us around the apartment. Hanging on the rear of the door to his bedroom was a black iron cross about fifteen inches long.

“What is this?” I asked.

“Oh, Lucceta’s family was given this cross by an important political figure, maybe Benito Mussolini.”

“It glares right at you when you close the door. Doesn’t it give you the creeps?”

“I see a blank door,” he replied.

Bucky was unhappy with the commute to Ward’s Island. He applied for, and was accepted to Creedmor Hospital in Queens, NY. From Creedmor, his gifted connection to troubled youths awarded him the Directorship of the Outpatient and Inpatient programs at Queens Children’s Psychiatric Center. He bought an upscale home in Kings Point, NY. Since Lucceta did not drive, she felt isolated in the community.

They bought an elegant apartment on Fifth Avenue, opposite The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bucky called one day and invited Sheila and I to visit him. We rang his bell. He opened the door, stepped into hall wearing only white jockey shorts. Of course, Lucceta wasn’t home. I suspect that this was his way of neutralizing the stuffy refinement of the building.

In 1992, he called and asked if Sheila and I would come to see him. When we arrived, we saw a frail Bucky lying in bed. Lucceta was feeding him ice cream. He asked if I wanted his car.

“I’m dying of pancreatic cancer,” he said.

He died the following day, Nov.17, 1992.

Neither Bucky’s mother nor father lived to see him become a successful doctor and father. For the complete story read, Cold Ground’s Been My Bed: A Korean War Memoir and Coming Home: A Soldier Returns Home From Korea by Daniel Wolfe. danielwolfebooks@aol.com

Daniel Wolfe

danielwolfebooks.com

914-961-570